Age Six: Making Good Use of the Sewers

A year later, Danielle was wheeling that same suitcase, but she had covered Babar with stickers of Wally Melson and Vance Gale. Mom was out of breath, having just come in from her run, and met Dani at the foot of the stairs. Dad calmly walked over from his computer in the study. They were used to her independent ways by now. I watched my sister with amusement, although leery of where we might end up this time.

“Danielle, don’t you have reports due for school?” Mom asked.

“This is my report,” Danielle replied. “I’m reporting for school.”

“And where might that be this time?” Dad asked.

“Zambia.”27

“Really?” Mom wiped perspiration from her forehead as she listened.

Dad seemed to guess immediately why Danielle was going. “Are you bringing a plane full of water?”

I recalled having heard about a great drought in Zambia.28

“Oh, I’ve got you one better than that,” Danielle replied.

“If you go now, you’ll miss Thanksgiving, Danielle,” Mom pointed out. “Can’t you put this off a couple of weeks?”

“No, no. The machines are arriving on Wednesday. I have to be there. Anyway, they don’t celebrate Thanksgiving. They’re concerned with water, not turkeys.”

“This is Danielle’s way of giving thanks,” I offered.

“You say you have machines?” Dad asked.

“Yeah, I have a hundred Slingshot machines29 arriving.”

Dad thought this over. His creased eyebrows relaxed, and a half smile crept over his face. “That’s a pretty fine idea, Dani.”

“Isn’t it? Each machine can provide clean water for a hundred people,” Danielle said.

“But where are they going to get the water for the machines to clean?” Mom asked.

“From the sewer,” Danielle replied, as if it were obvious.

“Ick,” I said.

Mom thought this over. “It sounds unappealing, but I guess that would work.”

“This is going to take some organization,” Dad said. “You can’t just drop-ship these machines. They could be stolen. And people need to be trained to operate them. And someone needs to collect the sewer water on a regular basis.”

Danielle’s tight-lipped expression seemed to say, Of course I’ve thought of all of that. “Oh, I’m working with a really nice man named Chibesa Bakala.”

Mom nervously rubbed her fingers, and looked in Dad’s direction.

“Not everyone in Zambia is reliable,” Dad said. “There are many war lords and bandits. What do you know about this gentleman?”

“He’s definitely not an outlaw. He’s the Commissioner of Natural Resources.”

“You know they have crooks in the government, too,” Mom said, biting her lower lip.

“Yeah, sure, I know that. But not this guy. I checked him out.”

“It wouldn’t hurt if we found out more about him. What do you say?” Dad said in a mild voice.

“Sure, go ahead.”

“You’re actually going for this?” Mom whispered to Dad.

“Won’t power be a problem, Dani?” Dad asked.

“The country isn’t as unstable as people think,” Danielle replied. “They just don’t have water.”

“I didn’t mean political power,” Dad said. “I meant electricity to operate the machines.”

“Oh yeah, I ordered Stirling engines,30 too. Each one makes enough electricity for one water machine.”

“But don’t those Stirling engines need fuel?”

“Sewage.”

“It looks like we’ll be making good use of their sewers!” I commented.

Danielle was well prepared for this interrogation. Mom, on the other hand, paced between the front door and the closet.

Dad asked more questions. “That’s about $200,000 of Slingshot and Stirling machines by my calculation. Who is paying for all this, Danielle?”

“I’ll have a grant from the World Health Organization.”31

“You applied for a WHO grant yourself?” Mom asked.

“Yeah, I’m sure it’ll come through. I mean I’ve got all their goals covered: Meets a basic unmet need. Minimal ongoing maintenance. Cost effective. Decentralized. There’s no way they’ll say no. I’ll get their official answer soon.”

“That’s certainly an appropriate place to apply to,” Dad admitted. “But you should never place an order before your funding is confirmed.”

“He means don’t count your chickens before they hatch,” I said.

Dani gave us all a determined look. “These chickens have to hatch. These people need clean water.”

Mom sighed in resignation. “I assume the Zambian government knows you’re six years old?”

Danielle glanced away. “I don’t think that’s come up …”

![]()

Danielle had arranged this great deal on tickets, but the catch was it was all middle seats. On the first leg from LA to JFK, Danielle was in the seat ahead of mine, so I kept seeing her head popping up and looking back at me with a big grin. Dad was in the back of the plane. That flight wasn’t too bad, but the red-eye flight to London was a bit more difficult. Dani was doing just fine, curled up in a little ball and sleeping like a baby. I, on the other hand, was up all night in between two overweight guys who seemed to be flirting with each other. I finally offered to change seats with one of them, which they were delighted to do, and that got me an aisle seat, but I still couldn’t sleep.

We then had a tight connection in London to catch a small propeller plane to Lusaka.32 We flew through a rainstorm and the plane bounced around like a ping-pong ball on the surf. Even Dad looked nervous. I alternated between being convinced we were going to crash to using all of my concentration to prevent myself from throwing up. Danielle was smiling like it was an amusement park ride.

As we landed, I could see a big sign that said Welcome to Zambia and another sign for Lusaka International Airport with a couple of missing letters. When I stepped off the plane it felt like a sauna, with searing gusts of sand swirling around. We were met by Commissioner Bakala, whom I recognized from his web picture, a heavyset bald man with a round face, a white hat, a black suit, and a smile as big as Danielle’s. He had one lanky young assistant dressed in some kind of traditional red robe, who was very eager to please us. He gathered up our bags and held an oversized umbrella to block the swirling sand.

“Ah, very well, Danielle has brought her family. We are greatly honored,” Mr. Bakala said in slow, carefully enunciated English.

Dad introduced Danielle.

“Oh, there is a little Danielle?” Mr. Bakala said.

Dani and I gave each other a look, wondering if he understood the situation.

“Perhaps your assistant would like to go with my assistant,” Mr. Bakala said to Dad, referring to me.

“No, thank you. Claire is my daughter,” Dad explained.

Flustered and embarrassed, the Commissioner replied, “Why, yes, of course.”

That, by the way, was not the first time someone had made that mistake. Every time this happened, my whole body burned, but then I’d look into the eyes of my family and remind myself that I belong. I know it, even if not everyone else does.

“And where is Danielle?” Mr. Bakala asked with an expectant expression.

“This is Danielle,” Dad replied.

“I mean the older Danielle,” the Commissioner clarified.

Dad gave him a wry smile. “Oh, there is only one Danielle.”

The Commissioner again tried to regain his composure.

![]()

The Slingshot machines started arriving at the airport in large wooden crates, but there were no Stirling engines. After some investigation by Commissioner Bakala, it turned out they had been seized by the Zambian Electric Power Commission.

“There are lots of fiefdoms in the government here,” Dad explained to Danielle.

“Unlike our government? I’ll go talk to the power commissioner then,” Danielle declared.

“Dani, you know what we’ve discussed,” Dad counseled. “It always pays to figure out who really makes the decisions and talk to him or her.”

“Yes, very good advice,” Mr. Bakala noted. “You should listen to your father, Danielle. And I can tell you who that person would be.”

Mr. Bakala took Danielle to meet with General Namusunga Lopa, the Chief of the Zambian Armed Forces while Dad and I remained in the background. Dani told me all about their meeting after the fact, and apparently the General was very impressed by such a confident and eloquent child.

We soon got a call from the Power Commissioner with profuse apologies for his misunderstanding. “The Stirling engines are on their way,” he reported.

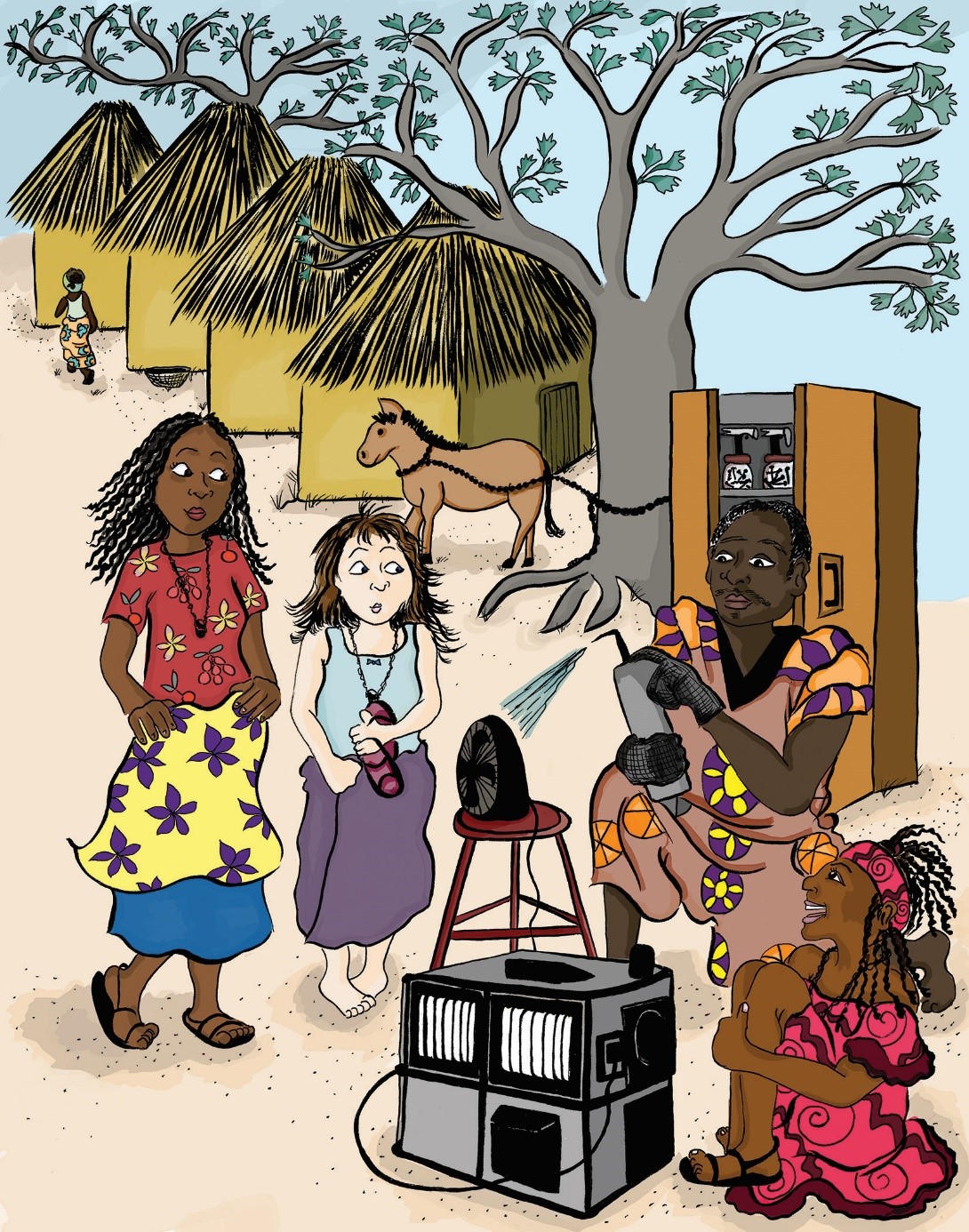

Mr. Bakala organized a group of volunteers in the town square to help Danielle assemble the machines, but they only spoke Nyanja,33 the principal language of Lusaka. The instructions for setting up the machines were terse and not very clear. Danielle had all the parts for one machine scattered on a concrete plaza, which was getting increasingly hot as the midday sun settled in the sky. The volunteers seemed eager, but were unable to read the English instructions. I handed Danielle parts as they started to put the unit together. She had particular difficulty trying to insert the compressor unit. It took a bit more force than Danielle could muster, and after several attempts, Mr. Bakala was able to get it to click in place. The rest of the assembly went fairly smoothly with the village girls eager to help in assembling the machine.

One of the girls poured the brownish, sour-smelling sewer water into the machine. It started to make a whirring sound, and after a few minutes, out came pure, odorless water! Everyone cheered. We all drank the water from plastic glasses that Mr. Bakala had brought for the occasion and Danielle curtsied for the group.

We were staying in a concrete building on metal beds with straw mattresses, but they were rather comfortable compared to sitting up on the plane. That night I could stretch out for the first time since leaving LA and fell into a deep sleep only to be awakened at the crack of dawn by the high-pitched braying of eight donkeys.

“We have most donkeys working in Africa,” Commissioner Bakala proclaimed as I looked out of the window. “We are ready for first field installation.”

The volunteers had fashioned rolling carts for two crates, containing one water machine crate and one Stirling engine. Each cart was pulled by one of the donkeys. There were also donkeys with saddles for Danielle, me, Dad, and two of the volunteers.

“We have a problem,” Dad said.

Danielle and I gave Dad a questioning look.

“Someone’s got to look after the machines in Lusaka,” Dad explained. “But I need to go with you two girls.”

“Mom will have an answer,” Danielle said.

And indeed, she did, as we spoke to Mom in a somewhat static-filled video call.

“I’ve had the same concern,” Mom said. “I already spoke with Uncle Eric, and he’s ready to fly in from Chicago. He says it sounds like a worthy cause, and he’s happy to volunteer a bit of time and the price of a plane ticket to help out.”

Eric is Mom’s brother who’s had an adventurous history as the manager of a forestry company in Northern Michigan. Both Danielle and I had been regaled with his tales of encounters with grizzly bears, and gangs of lumber thieves.

“That’s great. Eric will be fine to watch the machines. I’m glad he’s available,” Dad said.

“Actually, Richard, I’d be more comfortable to have him go with the girls. You can take care of the machines,” Mom replied. “He at least knows something about the forest.”

After that exchange, we waited two days for Uncle Eric’s arrival.

The two-day donkey ride was breathtaking as we passed a diversity of animals. From my pocket-sized book, African Wildlife in Pictures, I was able to identify pelicans, cormorants, herons, egrets, storks, osprey, big and little snakes, all sorts of small animals, antelope, and a pod of hippopotamuses. Feeling vulnerable, I looked intensely for lions, but Eric tried to assure me that he was pretty sure they were on the other side of Zambia at that time of year, and if we did encounter one to just remain calm. While I kept up my lion vigil, Danielle practiced her skills using a guitar simulator on her iPad. I must say that the speed and turns of her riffs were astonishing. On the first night of our two-day donkey trip, we camped out in a grass field under a fantastic quilt of stars we never see in Los Angeles.

We finally arrived in the small village of Sempala,34 and were met by a welcoming committee of three women in colorful blue and black dresses, and a girl about Danielle’s age.

“My name Amukusana. Me you call Amu,” the girl said in what was apparently her only English. She smiled as if Danielle was an old, lost friend. Danielle grinned back in kind. She gestured for Danielle to follow her and the two girls ran off giggling around a fat tree. It reminded me of how immediately accepting Charlie had been when I first met him.

“Icimuti,” Amu said as she pointed to the tree.

“Tree,” Danielle replied. “Dog,” Danielle said as she pointed to a village pet.

“Imbwa,” Amu replied in her native Bemba.35

Danielle tapped Amu’s shoulder and then ran away. Amu seemed to catch on quickly. The two girls ran their game of tag around the village, tapping and running, laughing and shrieking.

The volunteers were eager for us to unpack the donkeys and get settled, but I had never seen Danielle play with anyone like this before. I gestured that they should be patient. We let the girls continue their game, while I was given a tour of the town by a tall woman wearing thick eyeglasses and a bright red and yellow blouse.

The houses were single room huts with walls made of reddish brown wooden planks. “Kayimbi,” my guide said pointing to a wall, which I gathered was the type of wood. The roofs were pointed and thatched with straw. There were glassless wooden windows you could swing open. Inside were straw mats that served as beds. It looked like one or two families lived in each hut, which was luxurious compared to the brick room that Mum and I had shared with six other families in Haiti.

She showed me a large building with a crudely painted sign that said ANIM L B RN. I looked in, though my guide seemed eager to move on. There appeared to be no animals, but then I heard some scurrying and looked through a wire mesh window to find three chickens. I watched them do three wide circles around their pen. The largest one—I figured he must be in charge—pecked incessantly at the smallest one, who pecked at the one with a missing wing.

I noticed there were no men in the village. I asked my guide about this, but she didn’t understand, so I took out my pen and a pad and drew the stick figures for a man and a woman, pointed to the man and gestured “where?” She then made two gestures—showing me her necklace and then imitating someone striking the ground with a pick. I got the idea that the men were off working at a mine somewhere.

“Royal suite,” were the only English words my guide spoke as she showed me where they apparently intended Danielle and me to sleep. It was a hut like all the others, but it had two beds and featured the only wooden shelves I had seen in the village. I wanted to rest, but I was struck with a sudden concern for Danielle’s whereabouts. I tried to ask my guide where the girls were, but she did not understand, so I ran through the village. It was not long before I heard two girls giggling hysterically from one of the huts.

I walked in and there was Danielle with a big grin swinging a woven straw mat. Amu ducked and swung back. I picked up a mat similar to the ones that the girls were wielding and found it was surprisingly heavy and hard. That would not do—I needed to get them some real pillows, and fast. I didn’t see any nearby, so I conducted an urgent hunt for pillows in adjacent huts, but this was equally unsuccessful.

I looked up. There, hanging on a clothes line that traversed a dusty lot, were seven colorful blouses. I recalled that there was a pile of hay in the barn.

I’ll make my own pillows, I thought. But as I approached the clothes line I realized that I couldn’t just take a stranger’s clothes. I ran back to our royal suite, grabbed two of my blouses, actually the only two that I had brought, ran back to the barn, filled them with straw, tied the ends with string and the arms to each other, and voilà: two rather colorful makeshift pillows.

I’ll always remember Danielle’s teary reaction when I presented her with my creations.

Thank you, Claire, she mouthed, grabbing the flowery one. She ran after her new friend with her new pillow, and I tossed Amu the other one. As the pillow fight raged on, I slipped out to stroll through the nighttime village. The darkness was lit with candles and gas lanterns and all was remarkably tranquil despite my lingering lion concern.

When I came back to check on them, the girls were asleep arm in arm in Amu’s cot. My blouses had not fared as well as the girls—the fabric was ripped and stained, but I figured my wardrobe had been sacrificed to a good cause.

![]()

The next morning Danielle and Amu prepared to put together the two machines while video-recording each step with Danielle’s iPad.

“This is the input collection basin,” Danielle said, as she removed the first big piece from the water machine crate and placed it on a blanket while Amu held the iPad in video record mode. One by one the pieces ended up on the blanket as Danielle narrated. The girls then put the pieces back in the crate and Danielle recorded Amu taking them out and placing them on the blanket with her own narration in Bemba. Amu seemed to catch on quickly. Both Danielle and I wondered what Amu was actually saying as she took each piece out—we figured it was something like “big fat round bowl” and “long pointy thing.”

With my help, Danielle put the pieces together following the same procedure that worked so well in Lusaka, again with Amu video recording. Then Amu took it apart and assembled it with her Bemba narration and a bit of assistance from Danielle. The crowd of women watching us grew, along with anticipation as Amu tightened the last bolt. They followed the same procedure for the Stirling engine, which was much simpler as the motor comes preassembled. To prove that it worked, Danielle was able to illuminate a test light bulb, which got a cheer.

Danielle poured in the sewer water, which was not quite as scary as the foul fluid we used in Lusaka, but had its own strange odor. Danielle allowed Amu the honor of pressing the Start button. The machine jolted into action, but something was wrong. Danielle winced as we heard a grinding sound.

Danielle urgently pressed the Stop button and she and Amu began to disassemble the machine. The women watched with increasing concern. The water had already made its way through the mechanism, so the girls were getting soaked in the pungent liquid, which didn’t seem especially hygienic to me, but Danielle and Amu kept pressing ahead. Amu quickly identified the problem—a key assembly bolt had been inserted at an awkward angle.

“Argggh,” Danielle wailed as the head of the screw came off in her wrench. She looked forlorn as she realized that the bolt was buried deep in its shaft with no head to turn and no way to access it. Amu and the other women poked at it with spoons and small rocks, but Danielle urged them to stop, concerned it would only make matters worse.

Fifteen minutes later, Amu started jumping up and down and raising her hand suggesting she had a solution, said something in Bemba and ran off.

Danielle just sat there. “Just bringing another collection basin assembly will be too risky,” Danielle said to no one in particular. “I’d better bring a whole other water machine.”

“That would mean a round trip to Lusaka by donkey,” I pointed out.

Dani bit her lip and studied the machine again.

After about a half hour, she started slowly and sullenly taking the other assemblies apart. By the time she got down to the one assembly that was stuck with the jammed bolt, Amu came back, jabbering excitedly. She pointed off in the distance. We looked up but there was nothing to see—just the sun’s intense rays dancing on the hot, swirling sand.

But then, like a mirage in the mist, a tall bare-chested man emerged slowly leading a donkey, his image gradually coming into view as he drew closer. He had bright wide eyes and a mustache, and tied onto the donkey was a large ragged suitcase held together with string, along with a giant shiny metal box. Amu ran up to him and they hugged.

“Nsishumba,” Amu said pointing to the man and to herself. I quickly realized that Nsishumba was his name and that he was Amu’s dad, Nsishumba Mwanza. Danielle curtsied to him, which later became a signature move for her whenever she wanted to show someone deep respect. He strode to his suitcase and took out three necklaces, each consisting of a beautiful woven braid and a pendant of richly colored dark blue lapis lazuli, which he presented to Amu, Danielle, and me.

He took down the shimmering container which was taller than Danielle and unlatched it. Inside was a fantastic array of every sort of tool—wrenches, screwdrivers, saws, hammers, pliers, welding equipment, and strange gadgets I had never seen. Danielle and Amu showed him the problem. He tried a tool that was able to wrap itself around the bolt, but the size was not quite right. He tried many different sizes until finally a grin crept over his face, which was quickly returned by Danielle and Amu. The tool was able to slip inside the sleeve and wrap itself around the bolt.

He turned a knob, tightening the mechanism around the bolt, and then attempted to rotate it, but it wouldn’t budge. He kept turning it, with the strain showing on his face and his biceps. Danielle looked concerned that something was going to break. He tried again, but it just wasn’t moving.

Finally, Nsishumba gestured that he had an idea. He took out an acetylene torch and heated the bolt for about half a minute. He then pointed to the tool and said a few words in Bemba to his daughter. Amu gingerly turned the tool and lo and behold it now turned easily. Within seconds, the stuck bolt was removed.

But now there was another problem. They had no replacement bolt. Danielle found the head of the bolt that had broken off at the bottom of the water machine and made a gesture indicating that we just needed to connect it back to the bolt shaft. Nsishumba smiled and went back to his treasure trove of tools, this time selecting a small welding machine. But—he held up the plug—he needed an electrical outlet.

Danielle lit up and pointed to the female outlet on the Stirling engine. Nsishumba’s eyes widened as this was the first time he had ever seen an electrical outlet in Sempala. He plugged in his welding machine and Danielle started up the engine. The ready light came on. An expression that said Now we’re getting somewhere was on everyone’s faces. In a few more minutes, Amu’s dad welded the head back onto the bolt.

Amu inserted it, turning very slowly to make sure it went in straight this time. The two girls put the rest of the assemblies back together taking turns assembling and video recording. Amu had very quickly become an expert on Slingshot machine assembly. She invited her dad to pour in the dirty water. Everyone was silent as Amu gently pushed the Start button. This time, the machine began its gentle purr. Thirty seconds later, crystal clear water poured from the spout into the ceramic bottles the women had ready. There were cheers and tears of joy while Danielle and I shared a satisfied smile. I thought to myself: A father is a good thing to have.

![]()

On our way back to our royal suite, I stopped to show Danielle the animal barn and the three chickens. Danielle immediately shared my affection for them, giving the big chicken the name Loleck, because she seemed to laugh every time she poked the little chicken. I named that smaller chicken Boleck because she seemed to walk with a bow-legged limp. Boleck picked on the chicken with the broken wing, whom Danielle named Roleck because she would roll across the coop each time Boleck pecked her. Danielle became incensed as Boleck kept picking on Roleck, so Danielle picked up some seeds and, just as Boleck was about to peck Roleck, she threw a seed at her which startled her and prevented the attack. It took a few such interventions for Boleck to get the message, but it seemed to work. Then she saw Loleck headed for Boleck so she used the same strategy. By the time we left the chicken coop, the three chickens were sitting peacefully together. I joked, “We should send you to the Middle East next.”

“Great idea, Claire,” Danielle replied. “You think I can use the same strategy?”

![]()

The next day, Danielle and Amu held master classes for the women on how to use the two machines, while I passed the day wandering around the village. Again and again I saw Danielle rush urgently to the village outhouse.

“Dani, our toilet paper roll is getting dangerously thin. We only brought one. It needs to last until we get back to Lusaka. Or maybe we should start collecting leaves as plan B.”

“Thank you, Miss Calico,” she responded, as if I were a scolding teacher, “I’ll definitely take your concern into consideration.”

Our meals were almost all vegetables. Lunch was a stew of tomatoes, cabbage, eggplant, and onions with strong spices. I recognized ginger, paprika, and chili powder, but there were some unidentifiable other flavors in the mix. It was tasty and seemed to agree with my digestive tract, but Danielle’s stomach had its own ideas. There was always a dish of cornmeal paste, which was bland but filling. My favorite part of each meal was the compote of fruits which looked strange but tasted like mango, pear, and passion fruit.

Amu came up to me eagerly and shared another English phrase she had learned. “Celebration tonight,” she said.

Danielle ran up after Amu and nodded enthusiastically. “It’s for the water machine,” Danielle explained.

On the walk back to our royal suite, Danielle and I checked in on our new animal friends. Danielle ran up to the chicken coop and curtsied to Loleck with a smile that quickly turned to dismay as she looked inside.

“What’s the matter, Dani?”

“Oh my god, Roleck is gone,” I said answering my own question. “Boleck must have finally gotten to him.”

“Maybe Boleck was mad from my little discipline session,” Danielle added.

We stared at the coop hoping Roleck would magically appear.

I started to count the metal loops in the mesh, and that reminded me of counting the white tiles in the hospital when Danielle was born.

“Actually, I don’t think Boleck had anything to do with it,” Danielle concluded as we morosely left the coop.

As we made our way back to our room I began to fret about something else. The only two blouses I had brought were wrecked so I considered how to spruce up the T-shirt I was wearing. I eyed some wildflowers that I imagined I could attach if only I had some pins. I picked one that I recognized as a “blazing star” from my botany class and tried to insert it in the T-shirt’s neck opening but that looked outlandish even before the flower fell apart. Maybe I can just carry some flowers to make myself look more festive, I thought.

But when I got to our hut, there, neatly folded on my bed, was a beautiful red, yellow, and orange blouse with images of Zambian fruits and flowers.

“Hey Dani, do you know anything about how this got here?”

She widened her eyes as if to say Beats me, I have no idea. But I didn’t believe her.

![]()

Women in dresses with bold and intricate swirls of red, black and gold were sashaying around the room as we walked in. Danielle wore a light blue skirt with images of a five-pointed white and yellow flower I’ve seen all over Zambia. Someone must have given it to her as I had not seen it before. A band of four women consisting of three drummers and a marimba player played a song that made me think of the Mad Hatter jumping frenetically around the tea table. A dozen children danced with remarkable synchrony. There were candles on the tables and garlands of flowers hanging from the rafters. I saw only kids and women, with the exception of Nsishumba, who wore a traditional vest that came down to the floor decorated with images of colorful shields.

“Dad go back mine,” Amu said sadly but proudly in her improving English. She held up her lapis lazuli pendant to make the point about the mine.

The first course consisted of long pieces of what looked like celery but tastier and crisper, served with a spicy cold dip that tasted like hummus with some sort of crunchy nut in it.

The women serving us lit up, as if something profound was about to happen. They whispered to each other like excited school girls and ran to the neighboring tent—the kitchen—to fetch the next course.

Ceremoniously, they carried out the pièce de résistance of the evening. They looked eagerly at our faces for a reaction to the delicacy they had placed in front of us. Women from the neighboring table, including Amu’s mom, came over to our table to catch a glimpse. Apparently, our head table was the only one to get this version of the entrée—a lovely jubilee of rice, corn, tomatoes, and something like eggplant. But at our table, there were also small chunks … of chicken!

“I told you Boleck wasn’t responsible,” Danielle whispered in my ear.

“Maybe we can just slip the remnants of our friend into our pockets,” she added.

But this proved impossible with the women eagerly watching over our shoulders. Gingerly, we each cut a small piece of chicken into yet smaller pieces and put one in our mouths and swallowed.

Thirty seconds later, Danielle’s face turned green and she urgently pointed out of the tent toward the outhouse.

“You go,” I said to Danielle, feeling a bit queasy, but thinking I could wait it out. But I couldn’t. We both made a beeline for the outhouse. I usually try to resist this urge to purge, but feel better after I admit defeat—I got to the hole in the wooden plank that serves as a toilet barely in time and what little I had eaten came back up the same route it went down. Danielle was not quite as fortunate and threw up all over her skirt.

Exhausted, the two of us lay hand in hand in the outhouse. I thought maybe Danielle would have one of her crying fits, but instead she started to laugh at the incongruity of our situation, taking in the warm air, and closing her eyes.

![]()

“We’d better think about returning to the party, Dani,” I said, regaining my wits. Danielle’s eyes were closed but she nodded like that would be a good idea.

“Our next problem is cleaning you up,” I added, and took Danielle’s hand. I led her to the stream, grabbing a towel hanging on a clothes line en route—which I figured would be okay under the circumstances.

“This water is polluted,” Danielle noted.

“Right,” I replied. “We wouldn’t need the water machines if it were drinkable. But it should be okay to clean you up. Just don’t drink it.”

“Oh god, this is cold,” Danielle exclaimed as she waded in. She took off her skirt and we both cleaned it in the water using the big plantain leaves that lined the stream as scrub brushes. Gradually the stains disappeared.

“We just have one problem left,” I said as Danielle ran out of the water wrapping herself in the towel.

“Yeah,” Danielle responded holding up her dripping wet skirt.

“Dannel! Clear!” we heard a man shouting followed by what was obviously Amu’s voice, “We look for you.”

“Over here,” I answered, and with that Amu and her dad came running around the bend. Amu had her hands on her hips as if to say Where the heck did you go? Danielle held up her dripping wet skirt and Nsishumba immediately grasped the problem and held up a finger. I figured that meant he had a solution.

He gestured for us to follow him. Danielle limped along holding the towel around her and lugging her shoes while I carried the skirt.

We were back at the tool chest and the two machines. He took out the acetylene torch that had caused all three of us girls to frown, but he shook his head gesturing that this was only part of the solution. He retrieved a fan from the tool box, plugged it into the Stirling engine (which Amu turned on) and held the fan just past the point of the flame, and voila, a makeshift hot air dryer.

![]()

“I hope they didn’t save our chicken entrees for us,” I whispered to Danielle on our walk back to the party. She grimaced. But my fears were unfounded as they had moved on to dessert. There was a cheer as Amu and Nsishumba returned with the two of us in tow. The dessert was a fruit cake—the first cake we had seen in Sempala. It was the best treat we had had there and we dived into it robustly, much to the delight of our hostesses.

The next morning I was groggily regaining consciousness when Amu burst in exclaiming, “I go Danielle.” Danielle was one step behind her resolving any ambiguity in Amu’s slowly improving English.

“But there’s no donkey for her,” I replied, gradually regaining consciousness.

“Two seats!” Amu replied.

“Yeah, well two saddles,” Danielle clarified. “We just tried it. And, anyway, we need to edit our instructional videos. There’s a showing when we get back to Lusaka that Commissioner Bakala said he would organize.”

“And how is Amu going to get back to Sempala?” I queried.

“Eric will take us,” Danielle replied. “He has to return two of the donkeys anyway as they belong here.”

“Okay, but I don’t think you’re going to get much video editing done on our trip back,” I concluded.

We said our goodbyes. Amu’s parents embraced Danielle. Nsishumba was also leaving by donkey with his tool chest and suitcase, but headed to the mine where he worked. Women crowded around the machines and many hands waved to us as our caravan left the village.

It turned out I was wrong about the editing. While I held on for dear life, trying not to fall off my donkey and negotiating with my GI tract, which was definitely not happy with the donkey’s gait, the girls busily edited their videos while laughing and even recording additional video segments.

“Make sure you put the third basin screw in straight and turn it slowly,” Danielle said as Amu filmed. Then Danielle held the iPad and filmed Amu nodding in agreement with what Danielle had just said. Then they fussed with the video app, inserting the new segment in the right place. Amu was picking up iPad video editing skills to match her rapidly growing proficiency in English. Both girls seemed completely oblivious to the fact that they were riding on a donkey. Dani seemed as relaxed as she would have been sprawled out in our living room in Los Angeles. I was far less relaxed and stayed on the lookout for lions.

“Dani, you’re going to run out of battery,” I shouted at her.

Danielle held up a satchel. “Five batteries!”

“No wonder your luggage has been so heavy,” I replied.

![]()

As our caravan approached our inn in Lusaka, Danielle and Amu jumped off their donkey and ran to Dad who waited outside for our arrival. Danielle gave him a big hug and introduced Amu.

“He’s got a tool for everything!” Danielle said to Dad about Amu’s dad as I caught up with them.

It was a good thing the girls had edited their videos because scarcely an hour after our return to Lusaka a large group of volunteers, both men and women, assembled to watch and learn.

“Shouldn’t we vet this?” Dad asked.

“I’ll show you five minutes, but there isn’t time now to watch the whole thing. You’ll see it with the Commissioner.”

The screenings were a big success. In the film, after each phase of assembly, Danielle and Amu struck poses to demonstrate the configuration of the levers and pulleys, while a snippet of LaDonna’s “Pose” played in the background. They used decals on their arms and legs to show the position of screws and bolts. This generated laughter, but Amu’s Bemba version appeared to be even funnier—judging by the response of the mostly female audience. The editing seemed rather professional considering that it had just been completed hours earlier by two six-year-old girls riding on the back of a donkey in the Zambian jungle.

![]()

“There is a little problem, but nothing to worry about,” Commissioner Bakala told us. “It appears that thirty of the water machines had been stolen by bandits. We are trying to figure out which police district has jurisdiction. I hope it is not the Muchinga District. There is much corruption there,” he added.

“They’ll sort this out,” Dad counseled. “Our flights are tomorrow, and we really need to get back. I think we’ve accomplished our mission here.”

Danielle just stood there. She and Dad held a familiar staring contest, which Danielle always won.

“Okay, let’s find the police commissioner,” Dad replied.

The main police station turned out to be only a few blocks away.

“We’ve been expecting you,” the Commissioner greeted us as we entered the station. “We’ve been looking into this, but the machines do not appear to be in our district. We did intercept one attempt to sell the parts. Apparently, they were trying to get 250,000 kwacha.”

“That’s so inefficient,” Danielle exclaimed. “The machines cost us a thousand dollars each and they’re selling the parts for forty dollars!”

“Crime is rarely efficient, Danielle,” Dad explained. “That’s one reason it’s a crime.”

As we left the station, Dad kept an eye on Danielle, who was staring off into the distance.

“Okay, I’m going to the hotel to pack. Let me know when you’re ready to leave,” Dad said.

Eric and I stayed with Danielle who just sat looking dismayed but determined at the same time. After a few attempts at suggesting solutions to Danielle, we resolved to just sit with her as late afternoon set in.

Suddenly, a military convoy pulled in to the town square, spreading dust in all directions. A formation of soldiers stepped out of their jeeps and ceremoniously opened the door of an elaborate armed vehicle. Out strode Commander Lopa. Danielle ran up to him and he extended his hand which Danielle shook vigorously.

“Ah, just the person … I wanted you to know that we have declared the missing water machine situation to be a matter of national security. The army has been put in charge of the problem. We have already recovered five of the machines and apprehended several of the bandits. My men …”

“And women,” Danielle added.

“Why, yes of course.” The commander continued, “They are scouring the nation—trust me, we will find every part of every machine.”

Danielle wrapped her arms around him, which seemed to please him.

“We can go now,” Danielle whispered to me.

By the time we were ready to leave, several donkey convoys were getting ready to take machines to remote villages, while other machines were being loaded into a jeep to go to a nearby city.

![]()

When we got back to Los Angeles, we learned the disposition of Danielle’s funding application to the World Health Organization. It had been approved, but only for 70 percent of the cost.

Danielle raised the remaining $60,000 on the crowdfunding site GoFundMe posting funny and poignant videos of her and Amu lecturing the grown-ups on how to assemble the water machines.

![]()

“We didn’t do much,” Danielle said at the dinner table.

“Hey that’s an improvement over ‘we didn’t do anything,’” I noted.

“It sounds like thousands of people have clean water now who were drinking contaminated water before,” Mom said. “That’s something to be proud of, not mope about.”

“Danielle is always looking at the glass half empty rather than half full,” Dad observed.

Danielle sighed. “By my calculations, the glass is now about one third of one percent full.”

“That’s a lot, Danielle,” Dad countered. “The Talmud36 says ‘whoever saves one life has saved the whole world.’”

She perked up slightly. “The Talmud says that? Okay, but a million people in Zambia are still without clean water.”

“Danielle, you can’t solve all of this by yourself. Anyway, you’ve contributed more than just some machines,” Dad pointed out.

“Like what? Amu’s and my instructional video?”

“You gave them the most valuable thing of all, a good idea,” Dad explained. “Others can follow in your footsteps.”

“We’ll see,” Danielle said. “Mao37 once said he felt he was only moving a few deck chairs around on a sinking ship. He didn’t feel he was having much impact.”

“Too bad Mao didn’t stick to moving deck chairs around,” Dad replied. “Impact is not as important as having the right ideas. If one percent of the world did as much as you, there would be no suffering.”

Danielle shrugged her shoulders.

“I hear you made a friend, Danielle,” Mom said with a smile.

“Yeah, how about that,” Danielle replied. “Will miracles never cease?”

“I’d love to meet her.”

“Hey, not a problem,” Danielle offered. “All you have to do is hop a plane to New York. And then a red-eye to London. Then don’t dally in London, because it’s a tight connection to the old propeller plane to Lusaka. And you should hope that it’s not raining so that the flight isn’t too bumpy. You should bring a good nausea medicine, just in case. When you arrive, you need to arrange a donkey caravan, which you can’t reserve in advance since they have no phones, let alone Internet. After that, it’s a two-day donkey ride through the jungle to Sempala. Oh, and make sure you have a good guide because Sempala is easy to miss.”

“And watch out for lions,” I added.

“And if Amukusana’s not on a mission to gather swamp or sewer water,” Danielle concluded, “then you can say hi.”